Sociological Impacts of the Opioid Crisis on the Family

- Commentary

- Open Access

- Published:

The opioid crisis: a contextual, social-ecological framework

Health Inquiry Policy and Systems volume eighteen, Article number:87 (2020) Cite this commodity

Abstract

The prevalence of opioid use and misuse has provoked a staggering number of deaths over the past two and a half decades. Much attention has focused on individual risks according to various characteristics and experiences. Notwithstanding, broader social and contextual domains are likewise essential contributors to the opioid crisis such equally interpersonal relationships and the conditions of the customs and social club that people alive in. Despite efforts to tackle the effect, the rates of opioid misuse and not-fatal and fatal overdose remain loftier. Many call for a broad public health arroyo, but articulation of what such a strategy could entail has non been fully realised. In club to improve the sensation surrounding opioid misuse, nosotros developed a social-ecological framework that helps conceptualise the multivariable risk factors of opioid misuse and facilitates reviewing them in individual, interpersonal, communal and societal levels. Our framework illustrates the multi-layer complexity of the opioid crisis that more completely captures the crisis equally a multidimensional issue requiring a broader and integrated approach to prevention and treatment.

Background

The alarming rise in opioid misuse over the past two and a half decades has resulted in a public health crisis, characterised about prominently by a dramatic increase in drug overdose deaths. In 2017, approximately 12 million Americans misused opioids [ane] and more 47,000 people died of opioid overdose [2]. This overdose fatality charge per unit reflects an increase of 345% between 2001 and 2016 [3], with particularly steep annual increases in overdose fatalities since 2015. The growing opioid misuse result was recognised equally a national public health emergency by the United States Section of Health and Man Services in 2017.

Over the terminal several years, opioid misuse gained the attention of scholars, researchers, wellness professionals and politicians [4]. Many accept called for a broad public health approach, but the total breadth of such a strategy has non yet been articulated or realised. While diverse interventions have been implemented over time, they accept by and large been insufficient to slow the growth of non-fatal and fatal overdoses at a national level [5]. Interventions that only target a single aspect of the issue, such as restricting opioid supply, volition not be sufficient to ameliorate the opioid epidemic. This is further complicated by the speedily evolving nature of the epidemic. For example, the widespread availability of fentanyl and fentanyl analogues beginning around 2013 has resulted in a steep escalation of overdose death rates, even as other public health indicators (due east.g. prescription opioid misuse) have begun to ameliorate.

Furthermore, although the years of steeply escalating fatalities have brought newfound attention to the harms of opioid misuse, this problem is not new. Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a disabling disorder with high levels of morbidity and bloodshed that has devastated families and communities for decades. Although the introduction of agonist treatments in the 1970s brought critical relief to many people suffering from this illness, few people received any treatment even prior to the current crisis [6], while increasing criminalisation of drug employ diverted a high proportion of this population to the criminal justice arrangement. Thus, the inadequate public wellness and societal response to the harms of opioids is longstanding and new and expanded responses are sorely needed. The complexity of the crisis is represented by the multiple spheres of influence derived from individual factors, interpersonal relationships, and community and societal influences, indicating the necessity of a broader and a more integrated approach that includes prevention, treatment and overdose rescue interventions in addition to supply reduction strategies.

In this paper, we present a social-ecological framework as an of import step to conceptualise the complexity of the opioid epidemic. This framework can help inform the design of impactful interventions to curb the opioid crisis. We present our framework and provide a brief overview of the literature informing its components.

Social-ecological framework

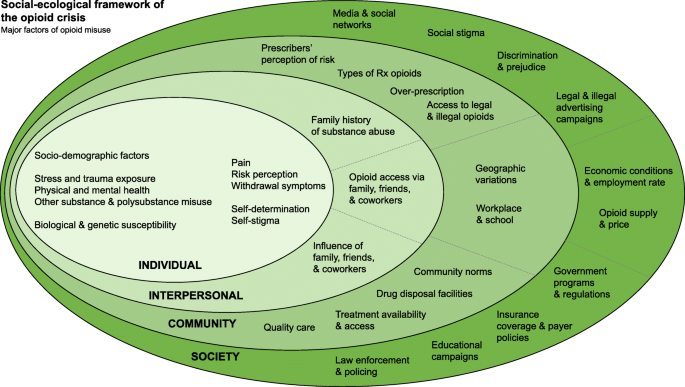

Our social-ecological framework, illustrated in Fig. 1, depicts the major run a risk factors for opioid misuse on 4 primary levels: the individual, interpersonal, communal and societal (see Additional file ane for our utilize of the term 'framework'). Each of these levels must be acknowledged to develop multifaceted and effective interventions to mitigate the opioid crisis. Post-obit social ecological paradigms [7], prior research has presented frameworks for substance use [8] in general and alcohol apply [ix] in particular. While there are similarities among these frameworks and ours, in that location are essential factors related to opioid misuse, such as the existence of both legal (i.due east. via legitimate prescription) and illegal supply sources and the availability of highly effective medications, that we discuss in this article. In the following sections, we provide a brief overview of how these levels of factors contribute to the opioid epidemic.

Social-ecological framework of the opioid crisis. Socio-demographic factors consist of age, race, gender, ethnicity, education, income and unemployment factors

Private level

Individual-level factors in opioid misuse and OUD span sociodemographic, health and mental wellness, biological, and psychosocial domains. Private factors can influence every aspect of the spectrum of opioid use and misuse, including the likelihood of exposure to opioids, initiation of opioid misuse, the development and maintenance of OUD, entry to and appointment in treatment, and relapse following an attempt to quit. These factors are complex, often collaborate and, in some instances, can be both a cause and consequence of opioid misuse (e.g. financial strain).

Many sociodemographic factors interact with opioid misuse, with implications for identifying at-gamble populations. Opioid misuse peaks in early adulthood (approximately eighteen–25 years) [x]. Early initiation of opioid misuse is a meaning take chances factor for the development of OUD [xi] and, thus, adolescence and young adulthood are key run a risk periods for opioid misuse. Gender tin as well play a role in risk for opioid misuse. For example, women are more likely than men to receive an opioid prescription [12, 13] and sex differences in the pharmacological effects of opioids have been demonstrated [14]. Critically, opioids are known teratogens and untreated OUD presents risks to both neonatal and maternal outcomes [fifteen].

Race as well plays a circuitous function in the opioid epidemic. People identified equally non-Hispanic white are more probable to receive an opioid prescription, increasing the adventure of exposure via this route [16]. Disparities in healthcare for hurting often get out pain untreated or undertreated in racial and ethnic minorities [17]. Although the opioid epidemic initially predominantly affected non-Hispanic whites [18], opioid overdose is chop-chop increasing amid racial minorities [19]. Race also impacts access to treatment; the vast majority of studies suggest, unsurprisingly, that racial and ethnic minority groups have less access to treatment. For case, studies show that admission to effective medication for OUD is lower in communities with higher African American and Hispanic populations [xx, 21]. Ane study found that, among people in treatment for OUD, the vast majority did not receive agonist therapies and that opioid agonist prescriptions were modestly college in black and Hispanic clients who used heroin relative to white clients [22]. Yet, many other studies suggest that racial and indigenous minorities face up disparities in access to care such as delayed admissions to handling and lower likelihood of receiving treatment [18, 23]. Another essential component of the role of race in the opioid epidemic is the disproportionate arrest and incarceration of people of color — we will discuss this further in the 'Societal level' section. Additionally, a wide array of health and mental health factors may increase the likelihood of hazard for misuse, some of which overlap with those that increment the likelihood of a prescription (e.g. pain). Pain is a cadre element of the opioid crisis and the majority of people seeking treatment for prescription OUD written report first using opioids for pain with a legitimate prescription [24]. Similarly, mental health factors are a pregnant contributor to opioid misuse. The majority of people with OUD as well suffer from a mood or anxiety disorder [25] and psychiatric symptoms are associated with incident take a chance for prescription opioid misuse [26]. Additionally, a history of other substance misuse and other substance utilise disorders is a significant take chances factor for opioid misuse; it is the most robust predictor of opioid misuse in people with chronic pain [27]. Similarly, polysubstance employ increases the risk of opioid misuse [28] and recent inquiry shows that it is highly prevalent among those with OUD [29].

A number of biological factors and genetic susceptibility tin can also predispose individuals to develop OUD. In addition to biological vulnerability to substance use disorders in general [30, 31], factors that influence the effects of opioids include genetic factors that modify the opioid receptors in the brain [32, 33]. Once physiological tolerance is developed to an opioid, decreases in dose or removal of the medication will result in withdrawal symptoms [34]. Although these symptoms are not fatal, they are extremely aversive and a significant reason for continued opioid utilise and relapse in people with OUD [35]. Indeed, over the course of OUD, the primary reason for use tends to shift to avoiding/relieving withdrawal more than managing pain or feeling good [24].

In this section, nosotros take highlighted some key individual-level factors; however, it should be noted that the they are not meant to be comprehensive. A broad range of other psychological and temperamental factors tin can as well play a office in the opioid epidemic; these include factors such equally impulsivity [36], self-stigma [37] and self-decision [38]. Readiness for change is likewise another factor that is associated with entry into treatment [39] and the change process during the handling [40], although limited information suggest this may not be related to OUD handling outcome [41]. Overall, there is an essential need for more research on the role of these and other similar psychosocial factors.

Interpersonal level

Family, friends and co-workers significantly shape the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of individuals to influence the likelihood of individuals' initiation and misuse of substances [42,43,44]. A family history of substance utilize disorder can influence opioid misuse through both genetic and ecology factors. People who have a family member with OUD are 10 times more vulnerable to misuse and overdose on the drug themselves and youth witnesses of family member overdose are more prone to overdose themselves [45, 46]. Individuals with a family history of opioid use are at a higher risk of suffering from symptoms of opioid dependence and becoming severely dependent [47]. This may be particularly important for women, for whom the risk of opioid misuse is higher when a spouse or partner misuses opioids [48]. Opioid misuse is besides influenced by the accessibility to opioids from family, friends and/or co-workers. Approximately 70% of people who report non-medical opioid use reportedly obtained opioids from family unit members or close friends [49, fifty]. Co-workers can also exist a source of opioids since most 69% of people who misuse opioids are employed and 10% to 12% report drug use during working hours [51, 52].

Interpersonal relationships influence the actions of individuals to apply opioids and seek treatment. Parental disapproval of drugs discourages substance utilize and families are often the offset to detect drug misuse because of their sensation of substance history [44, 53]. Studies show that family support of recovery tin can increase the likelihood of receiving handling [49, 54]. The emotional back up from social supports tin can increase medication adherence and motivate patients during their treatment sessions [53, 55].

Communal level

The third level of our framework considers the communal settings and their contributions to opioid-related risks [56]. The community and the immediate context in which individuals alive affect their daily behaviours in significant ways. Variables such as geographic conditions, handling accessibility, medication disposal services, workplace environment, prescribers' perception of risk, over-prescription of opioids or nether-treatment of pain, types of prescription opioid formulations bachelor, community norms, and access to legal and illegal opioids are major hazard factors that can perpetuate opioid misuse.

Between 2006 and 2017, approximately 224 1000000 opioid prescriptions were filled annually in the Usa, which is virtually plenty to distribute across the unabridged United states population [57]. Over-prescription of opioids has been influenced by several interacting factors. Ofttimes, physicians' insufficient hurting management preparation and knowledge on opioid misuse chance contribute to their inability to safely prescribe opioids, implement and interpret risk assessments, notice addiction, and facilitate discussions with patients [58,59,60]. Furthermore, prescribers who overestimate the benefits and underestimate the danger of opioids are probable to contribute to over-prescription by providing months' worth of medication when only a few days may be needed for pain direction [61, 62]. The establishment of guidelines (e.g. the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain) and other interventions to better prescribing practices has resulted in decreases in opioid prescribing [63], with reductions occurring since 2010 [57].

Over-prescription was likewise influenced by pharmaceutical marketing campaigns that falsely marketed opioids as non-addictive and "create[d] value" for doctors by offering monetary compensations [64]. Doctors who refused to prescribe opioids to patients were labelled equally 'opiophobic' [65]. These incentives include sponsored meals, speaking fees, travel expenses and education [66]. Although just 7% of opioid-prescribing physicians received gifts from drug companies, they were more probable to prescribe opioids to their patients than doctors who did not benefit from the incentive [66]. Increases in prescriptions may take likewise reflected unintended consequences of advancement for the improved treatment of astute and chronic pain in the 1990s, which resulted in regulatory changes requiring the cess of pain as the '5th vital sign'.

Formulations of opioids also play a role in opioid misuse. Standard opioid pills can be crushed to attain a more than rapid effect via routes of administration such as intranasal or intravenous [67]. Despite the lack of sufficient supporting bear witness for the efficacy of abuse-deterrent drugs in preventing misuse, the United States Nutrient and Drug Administration has supported the evolution of such types of prescription opioids to address the growth in opioid-related abuse and deaths [68, 69]. The misconception that abuse-deterrent opioids are a panacea dangerously marks the issue as a pharmaceutical trouble rather than a complex one integrated by biological, psychological and social challenges [67]. Furthermore, abuse-deterrent opioids do non solve the long-standing problem of heroin and other illicitly produced opioids.

The illicit market is another significant source of misused opioids. Heroin is cheap and widely bachelor in about regions in the United States. Furthermore, in that location is a big online opioid market place, which enables customers to purchase unregulated opioids from the web [70, 71]. The increased availability of highly potent synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and fentanyl analogues, has contributed to the dramatic increase in rates of overdose deaths since 2015 [xix].

At that place has been substantial geographical variation in opioid misuse and overdose, which may exist attributable to a range of factors [72]. Not-metropolitan areas are known to have higher rates of opioid prescribing [73], perhaps because the rural population disproportionately consists of older adults and people employed in physically enervating jobs who may exist peculiarly susceptible to pain-related conditions [74,75,76,77]. Overdose deaths are more prevalent in not-metropolitan areas relative to urban areas [78].

Workplaces and schools are also important settings where individuals spend significant time. Some careers take particularly high rates of opioid misuse and are typically those characterised by demanding physical labour and/or easy access to opioids; individuals involved with construction occupations endure from the highest rate of opioid overdose [79]. Schools are likewise an important setting, given that adolescence is a meaning risk period and diversion of medication is common in this group [80].

Customs norms with respect to alcohol, tobacco and drug use can besides impact the likelihood of initiation of substance misuse [72, 81]. Finally, drug disposal and drove sites tin potentially deter misuse and discourage opioid diversion amongst patients' friends and family by restricting the available supply in households and communities [44].

Similarly, the availability and admission to handling are crucial for both the adequate management of health and mental wellness conditions that increase risks for opioid misuse (due east.g. hurting, psychiatric disorders) and for the effective treatment of OUD [82]. Despite ample prove about effective medications for the treatment of OUD [83, 84], they remain widely underutilised in the United States [85, 86] due to misperceptions nigh the efficacy of medications [87], policy and regulatory barriers [88], and lack of admission to addiction experts [89, 90], amongst others. Furthermore, access to care, and to prove-based care, varies across regions. The availability of high-quality care is as well impacted by societal factors (see beneath). OUD is associated with high rates of relapse and the type of care received has substantial implications for outcomes [91, 92].

Societal level

The major risk factors of opioid misuse are shaped by the larger social context, which encompass opioid supply and demand, government regulations, economic weather and unemployment rates, elements of the media, social stigma, bigotry and prejudice, advertising campaigns, educational campaigns, and police enforcement.

The market place economy of opioids is altered by the fluctuations in a drug'due south supply and demand. A tremendous increase in the supply and availability of opioids arose from the over-prescription, diversion and redistribution of the pills to family, friends and/or co-workers. This was exacerbated by pharmaceutical companies' extensive legal advertising tactics, which tin can lower consumers' perception of the risks of opioids and increase their knowledge on prescription drug availability [93, 94]. Over time, the epidemic intensified as illicit opioids flooded the market place and heroin became inexpensive [82, 95] — heroin is just a third of its price in the 1990s and remains cheaper than opioid prescriptions [96]. Indeed, over fourscore% of people who initiate heroin employ first started opioid utilize with prescription opioids [97]; cost is 1 of the near commonly reported reasons for this transition [98]. Opioid supply can be managed through reduced prescribing or increased apply of misuse-deterrent formulations, but these efforts can be challenged by unintended, short-term negative consequences. In particular, the decreased availability of prescription opioid analgesics tin lead to increases in the employ of illicitly produced opioids such equally heroin [67].

Government programmes and regulations related to opioids may accept many forms such as drug scheduling through the Drug Enforcement Agency, regulation of opioid prescribing practices (east.g. use of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs; PDMPs) [99] and Medicare/Medicaid regulations. Data support the potential value of certain policies such as Adept Samaritan laws [100], naloxone access legislation [101], and PDMP requirements [102]. Importantly, these dissimilar policies target different elements of the opioid crisis (eastward.g. overdose fatalities, prescribing practices). Regime regulations too have implications for treatment availability, every bit federal and state governments regulate accreditation and licensing requirements as well equally elements of training and service provision. For instance, the Drug Addiction Handling Act of 2000 requires that prescribers consummate boosted grooming to prescribe or manipulate buprenorphine. Likewise, government regulations require that methadone is only dispensed in licensed opioid handling programmes and cannot be used for the treatment of OUD in primary care, unlike in other countries.

The number of people who accept health insurance coverage varies past state and has implications for access to OUD handling. Medicaid expansion has played a significant part in access to medication for OUD; states that elected to expand Medicaid as function of the Affordable Care Deed had a more than than four-fold higher increase in prescribing of effective medications for OUD (specifically buprenorphine and naltrexone) relative to non-expansion states [103]. In addition to their contributions to the opioid supply, payer policies as well impact access to treatment for pain, psychiatric illness and OUD. For example, prior authority for buprenorphine prescribing has been presented equally a strategy for reducing diversion or other adverse events; however, this tin also present a meaning bulwark to care [104].

Social stigma, the misconception of substance misuse as a by-product of weak willpower and moral corruption, is a significant barrier to seeking help for opioid misuse [3, 49, 105]. Likewise, cultural and social behavior communication via media and social media can be either harmful (e.g. influencing an increment in substance use) [106, 107] or protective (eastward.g. increment public sensation nigh opioids and their potential harms).

The rise in 'deaths of despair' (typically referring to overdose and suicide fatalities) betwixt 1999 and 2015 has been linked to poor economic atmospheric condition [82, 108]. During macroeconomic slumps, every pct point increase in unemployment saw a iii.6% rising in opioid death rates and emergency visits. The fall in the employment rate resulted in lower life satisfaction and higher drug employ among the population [109, 110]. A recent working paper from the National Agency of Economic Research concluded that ten% of the rising in opioid-related deaths could be explained by recessions [111]. Even so, macroeconomic impacts on drug use are complex due to the many variables affected by poor economical conditions (e.k. drug prices, incomes, employment, etc.) [112].

Law enforcement and the criminal justice systems are other pregnant components of the response to the opioid crunch. Law enforcement (forth with other emergency responder groups) has been increasingly involved in overdose-rescue efforts. Some departments accept expanded these efforts to include linkage to treatment and other supports. Law enforcement also plays a function in policing of the illicit opioid supply [113]. Finally, opioids are controlled substances that conduct meaning criminal penalties for possession and distribution. Substance use disorders are common among incarcerated people and release from prison is associated with a significantly heightened take a chance for fatal overdose [114]. Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by the criminalisation of substance apply, rather than a public health approach. Additionally, those recently released from prison were more likely to die from overdose than those who did not face the law enforcement [82, 115].

Conclusion

The primary goal of this article was to emphasise that the opioid crisis is a multi-faceted and ever-evolving outcome, which requires the consideration of numerous interacting factors in developing interventions and evaluating their effectiveness. Although much of our focus in this paper is on contempo findings and trends, information technology is essential to note that the devastating bear upon of opioid misuse and OUD has been ongoing for decades. The complex and interacting contributors have evolved over time, yet many have been longstanding across each of these levels (east.m. individual, community). These factors intersect with several disparate stakeholder groups, including healthcare providers, government and regulatory agencies, insurers, and law enforcement and criminal justice, amongst others.

Although nosotros have organised our framework according to the individual, interpersonal, customs and social club contexts, we also recognise that at that place is substantial interconnectedness amidst these contexts. For example, access to opioids — a substantial contributor of likelihood of use — cuts across each of these contexts, including the individual (e.one thousand. presence of a pain condition), interpersonal (due east.thou. access to opioids from family or friends), community (eastward.g. availability of drug disposal resources) and guild (east.chiliad. PDMP laws). The ultimate utility of this framework is to utilise it to investigate the complex and multi-directional links amidst the factors that contribute to the ongoing epidemic.

The development of constructive opioid prevention and treatment interventions requires a broad analysis of the factors that ascend from multiple contexts (individual, interpersonal, customs and society). We conceptualised this complex system using the social-ecological framework presented in Fig. 1. As research continues to evolve on these factors and their contribution to the opioid epidemic, this framework tin be farther refined. The framework is also intended to provide context for the generation of testable hypotheses most these factors, their interaction and the impact of treatment or policy levers at each level on the opioid epidemic.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- OUD:

-

Opioid use disorder

- PDMP:

-

Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

References

-

Center for Behavioral Wellness Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Apply and Health: Detailed Tables. U.S. Health and Human Services; 2018.

-

Scholl L, et al. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419–27.

-

Gomes T, et al. The brunt of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180217.

-

Office of Boyish Wellness, Opioids and Adolescents, U.S. Washington, D.C: Department of Health and Human being Services; 2017. https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/boyish-development/substance-utilise/drugs/opioids/index.html. Accessed 15 Jul 2020.

-

Bart G. Maintenance medication for opiate addiction: the foundation of recovery. J Addict Dis. 2012;31(3):207–25.

-

Hser YI, Anglin D, Powers 1000. A 24-yr follow-up of California narcotics addicts. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 1993;fifty(vii):577–84.

-

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Printing; 1979.

-

Connell CM, et al. Social-ecological influences on patterns of substance utilise amidst non-metropolitan high school students. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;45(1–2):36–48.

-

Sudhinaraset One thousand, Wigglesworth C, Takeuchi DT. Social and cultural contexts of booze use: influences in a social-ecological framework. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2016;38(one):35–45.

-

Abuse S, Mental Wellness Services Administration. The DAWN report: highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Alert Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville: US Department of Wellness and Human being Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Wellness Services Administration, Middle for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2013. p. 64–72.

-

Schepis TS, Hakes JK. Historic period of initiation, psychopathology, and other substance use are associated with fourth dimension to use disorder diagnosis in persons using opioids nonmedically. Subst Abus. 2017;38(four):407–13.

-

Hirschtritt ME, Delucchi KL, Olfson M. Outpatient, combined use of opioid and benzodiazepine medications in the United States, 1993–2014. Prev Med Rep. 2018;nine:49–54.

-

Cicero TJ, et al. Co-morbidity and utilization of medical services past pain patients receiving opioid medications: data from an insurance claims database. Hurting. 2009;144(i–2):20–vii.

-

Comer SD, et al. Evaluation of potential sexual activity differences in the subjective and analgesic effects of morphine in normal, good for you volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208(1):45.

-

Lind JN, et al. Maternal apply of opioids during pregnancy and congenital malformations: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20164131.

-

Terrell KM, et al. Analgesic prescribing for patients who are discharged from an emergency section. Pain Med. 2010;xi(7):1072–7.

-

Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 2009. 10(12): p. 1187–1204.

-

Wu LT, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Treatment utilization amid persons with opioid utilise disorder in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:117–27.

-

Seth P, et al. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants—United States, 2015–2016. Am J Transplant. 2018;eighteen(6):1556–68.

-

Hansen H, et al. Buprenorphine and methadone handling for opioid dependence by income, ethnicity and race of neighborhoods in New York Metropolis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;164:14–21.

-

Stein BD, et al. A population-based test of trends and disparities in medication treatment for opioid use disorders among Medicaid enrollees. Subst Abus. 2018;39(four):419–25.

-

Krawczyk N, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder in a U.S. national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:512–viii.

-

Boudreau DM, et al. Documented opioid utilize disorder and its treatment in primary care patients across 6 U.S. health systems. J Subst Abus Treat. 2020;112s:41–8.

-

Weiss RD, et al. Reasons for opioid use amid patients with dependence on prescription opioids: the role of chronic hurting. J Subst Abus Care for. 2014;47(2):140–5.

-

Conway KP, et al. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-Four mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–57.

-

Sullivan Doctor, et al. Association betwixt mental wellness disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid utilise. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(nineteen):2087–93.

-

Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Clin J Pain 2008. 24(6): p. 497–508.

-

Morley KI, et al. Polysubstance use and misuse or abuse of prescription opioid analgesics: a multi-level analysis of international data. Hurting. 2017;158(vi):1138–44.

-

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Kasper ZA. Polysubstance employ: a broader understanding of substance utilise during the opioid crisis. Am J Public Health 2020. 110(2): p. 244–250.

-

Schultz W. Potential vulnerabilities of neuronal reward, risk, and decision mechanisms to addictive drugs. Neuron. 2011;69(4):603–17.

-

Swendsen J, Le Moal M. Private vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1216(1):73–85.

-

Nelson EC, et al. Association of OPRD1 polymorphisms with heroin dependence in a large case-control series. Addict Biol. 2014;19(1):111–21.

-

Gao X, et al. Contribution of genetic polymorphisms and haplotypes in DRD2, BDNF, and opioid receptors to heroin dependence and endophenotypes amid the Han Chinese. Omics. 2017;21(7):404–12.

-

Van Ree JM, Gerrits MA, Vanderschuren LJ. Opioids, reward and addiction: an encounter of biology, psychology, and medicine. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51(2):341–96.

-

Northrup TF, et al. Opioid withdrawal, craving, and use during and after outpatient buprenorphine stabilization and taper: a detached survival and growth mixture model. Addict Behav. 2015;41:twenty–8.

-

Aklin WM, et al. Chance-taking propensity as a predictor of consecration onto naltrexone treatment for opioid dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):e1056–61.

-

Hammarlund R, et al. Review of the effects of self-stigma and perceived social stigma on the treatment-seeking decisions of individuals with drug- and booze-use disorders. Subst Abus Rehabil. 2018;9:115–36.

-

Ayres R, et al. Enhancing motivation inside a rapid opioid substitution treatment feasibility RCT: a nested qualitative study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;9(i):44.

-

Langabeer J, et al. Outreach to people who survive opioid overdose: linkage and retention in treatment. J Subst Abus Care for. 2020;111:11–5.

-

Blanchard KA, et al. Motivational subtypes and continuous measures of readiness for modify: concurrent and predictive validity. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(1):56.

-

Gossop K, Stewart D, Marsden J. Readiness for modify and drug use outcomes afterward treatment. Addiction. 2007;102(two):301–8.

-

Collins D, et al. Non-medical use of prescription drugs amidst youth in an Appalachian population: prevalence, predictors, and implications for prevention. J Drug Educ. 2011;41(three):309–26.

-

Schroeder RD, Ford JA. Prescription drug misuse: a exam of iii competing criminological theories. J Drug Issues. 2012;42(1):4–27.

-

Substance abuse and mental health services administration, preventing prescription drug misuse. Overview of factors and strategies; 2016. https://preventionsolutions.edc.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Preventing-Prescription-Drug-Misuse-Overview-Factors-Strategies_0.pdf. Accessed fifteen Jul 2020.

-

Mistry J, et al. Genetics of opioid dependence: a review of the genetic contribution to opioid dependence. Curr Psychiatr Rev. 2014;10(2):156–67. https://preventionsolutions.edc.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Preventing-Prescription-Drug-Misuse-Overview-Factors-Strategies_0.pdf.

-

Silva Yard, et al. Factors associated with history of non-fatal overdose among young nonmedical users of prescription drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128(1–2):104–10.

-

Pickens RW, et al. Family history influence on drug corruption severity and handling consequence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61(3):261–70.

-

Powis B, et al. The differences between male person and female person drug users: customs samples of heroin and cocaine users compared. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31(five):529–43.

-

Hewell VM, Vasquez AR, Rivkin ID. Systemic and individual factors in the buprenorphine treatment-seeking procedure: a qualitative study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2017;12(1):3.

-

Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Sources of prescription opioid hurting relievers past frequency of past-twelvemonth nonmedical apply: United states, 2008-2011. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(5): p. 802–803.

-

SAMHSA, National survey on drug use and wellness: 2013 dress rehearsal terminal report UsH.a.H. Services, Editor. 2014. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DressRehearsal-2013/NSDUH-DressRehearsal-2013.pdf.

-

Albrecht Southward. The opiate addict in your part, heroin and pain pills in your workplace? Psychology Today. 2014. https://world wide web.psychologytoday.com/us/weblog/the-human action-violence/201402/the-opiate-addict-in-your-office. Accessed 15 Dec 2018.

-

Stumbo SP, et al. A qualitative analysis of family unit involvement in prescribed opioid medication monitoring among individuals who have experienced opioid overdoses. Subst Abus. 2016;37(one):96–103.

-

Gyarmathy VA, Latkin CA. Individual and social factors associated with participation in treatment programs for drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(12–thirteen):1865–81.

-

Daley DC. Family and social aspects of substance use disorders and treatment. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21(4):S73–six.

-

Center for Disease control and Prevention, The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention. 2018, Center for Affliction Command and Prevention.

-

Schieber LZ, et al. Trends and patterns of geographic variation in opioid prescribing practices by Country, United States, 2006-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190665.

-

Upshur CC, Luckmann RS, Savageau JA. Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):652–v.

-

O'rorke JE, et al. Physicians' condolement in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(2):93–100.

-

Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. North Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1253–63.

-

Kolodny A, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Wellness. 2015;36:559–74.

-

Makary MA, Overton HN, Wang P. Overprescribing is major contributor to opioid crunch. BMJ. 2017;359:j4792.

-

Bohnert ASB, Guy GP Jr, Losby JL. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention'southward 2016 Opioid Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(6):367–75.

-

The more opioids doctors prescribe, the more they become paid. Harvard T.H. Schoolhouse of Public Health 2018. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/opioids-doctors-prescriptions-payments/. Accessed xi Jul 2020.

-

Dhalla IA, Persaud Due north, Juurlink DN. Facing upwardly to the prescription opioid crunch. BMJ. 2011;343:d5142.

-

DeJong C, et al. Pharmaceutical industry–sponsored meals and doctor prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1114–22.

-

Leece P. Tamper-resistant drugs cannot solve the opioid crisis. CMAJ. 2015;187:717–8.

-

Nelson LS, Juurlink DN, Perrone J. Addressing the opioid epidemic. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1453–4.

-

Clinton Foundation, The opioid epidemic from evidence to affect. 2017. https://www.jhsph.edu/events/2017/americas-opioid-epidemic/written report/2017-JohnsHopkins-Opioid-digital.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2020.

-

The National Heart on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia Academy. You lot've Got Drugs!. Prescription Drug Pushers on the Internet. 2004. https://www.centeronaddiction.org/download/file/fid/556.

-

Forman RF. Availability of opioids on the internet. JAMA. 2003;290(seven):889.

-

Keyes KM, et al. Agreement the rural–urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid utilise and abuse in the Usa. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e52–9.

-

McDonald DC, Carlson Grand, Izrael D. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the US. J Pain. 2012;13(ten):988–96.

-

Glasgow N. Rural/urban patterns of aging and caregiving in the United States. J Fam Issues. 2000;21(five):611–31.

-

Hunsucker SC, Frank DI, Flannery J. Coming together the needs of rural families during critical disease: The APN'south office. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1999;18(3):24.

-

Hoffman PK, Meier BP, Council JR. A comparing of chronic pain between an urban and rural population. J Community Wellness Nurs. 2002;nineteen(4):213–24.

-

Leff M, et al. Comparing of urban and rural not-fatal injury: the results of a statewide survey. Inj Prev. 2003;nine(iv):332–seven.

-

Paulozzi LJ, Xi Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning bloodshed in the Us by urban–rural condition and by drug blazon. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(10):997–1005.

-

Harduar LM, Steege AL, Luckhaupt SE. Occupational patterns in unintentional and undetermined drug-involved and opioid-involved overdose deaths – The states, 2007-2012. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):925–thirty.

-

Boyd CJ, et al. Prescription drug abuse and diversion amid adolescents in a southeast Michigan school district. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):276–81.

-

Musick K, Seltzer JA, Schwartz CR. Neighborhood norms and substance utilize amidst teens. Soc Sci Res. 2008;37(i):138–55.

-

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Pain management and the opioid epidemic: balancing societal and individual benefits and risks of prescription opioid use. Washington, DC: National Academies Printing; 2017.

-

Wakeman SE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different handling pathways for opioid apply disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(ii):e1920622.

-

Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harvard Rev Psychiatr. 2015;23(2):63–75.

-

Volkow ND, et al. Medication-assisted therapies — tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6.

-

Larochelle MR, et al. Medication for opioid employ disorder later on nonfatal opioid overdose and clan with bloodshed: a cohort report. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137–45.

-

Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction handling programs. J Addict Med. 2011;5(1):21–7.

-

Clark RE, Baxter JD. Responses of state Medicaid programs to buprenorphine diversion: doing more than damage than good? JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1571–two.

-

DeFlavio JR, et al. Analysis of barriers to adoption of buprenorphine maintenance therapy by family physicians. Rural Remote Health. 2015;xv:3019.

-

Knudsen HK, Roman PM, Oser CB. Facilitating factors and barriers to the use of medications in publicly funded addiction treatment organizations. J Aficionado Med. 2010;iv(2):99–107.

-

McGlynn EA, et al. The quality of wellness care delivered to adults in the The states. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

-

Nunes EV, et al. Relapse to opioid use disorder afterwards inpatient handling: protective issue of injection naltrexone. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;85:49–55.

-

Nunes, E.5., et al., Relapse to opioid use disorder after inpatient treatment: Protective effect of injection naltrexone. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;85:49-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.04.016.

-

Strasburger VC. Policy statement--children, adolescents, substance abuse, and the media. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):791–ix.

-

Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Human relationship betwixt nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med 2016. 374(2): p. 154–163.

-

Felter C. The US Opioid Epidemic. 2017 Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-opioid-epidemic. Accessed11 Jul 2020.

-

Jones CM. Heroin employ and heroin utilise risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers–Usa, 2002–2004 and 2008–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1):95–100.

-

Cicero TJ, et al. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective assay of the by l years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(vii):821–6.

-

Haffajee RL, Jena AB, Weiner SG. Mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring programs. JAMA. 2015;313(ix):891–ii.

-

McClellan C, et al. Opioid-overdose laws clan with opioid use and overdose mortality. Aficionado Behav. 2018;86:90–5.

-

Gertner AK, Domino ME, Davis CS. Do naloxone access laws increase outpatient naloxone prescriptions? Evidence from Medicaid. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:37–41.

-

Strickler GK, et al. Effects of mandatory prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) use laws on prescriber registration and use and on risky prescribing. Drug Booze Depend. 2019;199:1–9.

-

Sharp A, et al. Impact of Medicaid expansion on access to opioid analgesic medications and medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Wellness. 2018;108(5):642–8.

-

Kermack A, et al. Buprenorphine prescribing practice trends and attitudes among New York providers. J Subst Abus Care for. 2017;74:1–6.

-

Olsen Y, Sharfstein JM. Confronting the stigma of opioid apply disorder—and its handling. JAMA. 2014;311(14):1393–four.

-

Hawton M, et al. Furnishings of a drug overdose in a telly drama on presentations to hospital for self poisoning: time series and questionnaire study. BMJ. 1999;318(7189):972–7.

-

Moreno MA, et al. Display of health adventure behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: prevalence and associations. Curvation Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(ane):27–34.

-

Example A, Deaton A. Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brook Pap Econ Human action. 2017;2017:397.

-

Hollingsworth A, Ruhm CJ, Simon M. Macroeconomic weather and opioid abuse. J Wellness Econ. 2017;56:222–33.

-

Nagelhout GE, et al. How economic recessions and unemployment bear upon illegal drug use: a systematic realist literature review. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;44:69–83.

-

Ruhm CJ. Deaths of despair or drug problems? Working Papers 24188, National Bureau of Economical Research, Inc. 2018. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/24188.html. Accessed 15 Jul 2020.

-

Bretteville-Jensen AL. Illegal drug utilise and the economic recession--what can we learn from the existing research? Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22(5):353–9.

-

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Combatting the Opioid Crunch D.o.H. Security, Editor. 2018, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. https://www.ice.gov/features/opioid-crisis. Accessed 15 Aug 2019.

-

Binswanger IA, et al. Release from prison house—a high risk of death for quondam inmates. Northward Engl J Med. 2007;356(ii):157–65.

-

Fellner J. Race, drugs, and police enforcement in the United States. Stanford Law Policy Rev. 2009;20:257.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would like to thank Miriam Boeri, Erin Stringfellow, Wayne Wakeland and Scott Weiner who provided constructive feedback on before versions of this article.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation and design: MSJ, RKM; Writing the first draft: MSJ, RCH, and RKM; Discussion, disquisitional review, and writing: MSJ, MB, RCH, HKK, and RKM. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher'south Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you lot give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary political party material in this commodity are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you lot will demand to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/aught/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Jalali, M.S., Botticelli, M., Hwang, R.C. et al. The opioid crisis: a contextual, social-ecological framework. Wellness Res Policy Sys 18, 87 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00596-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00596-viii

Keywords

- opioids

- opioid utilize disorder

- social-ecological framework

Source: https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-020-00596-8

0 Response to "Sociological Impacts of the Opioid Crisis on the Family"

Postar um comentário